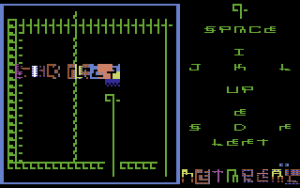

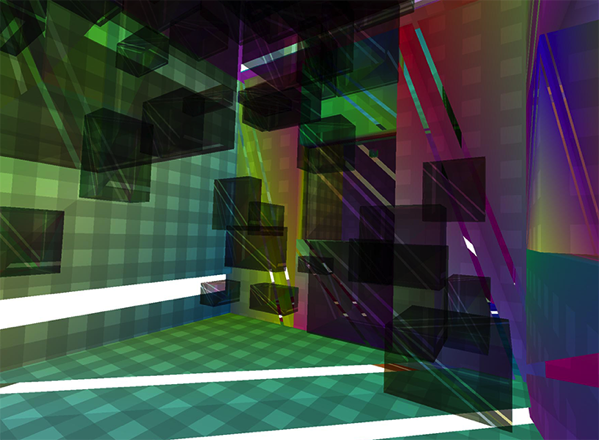

The Metareal World is very, very, rectangular.

The classic world is an 8×8 grid of rooms, each room described by a 12×12 grid of characters. (Each room was checkered with two characters and a color scheme.) Your probe could only move exactly up, down, left, right. Most objects also moved only cardinally. (1)

I took a wonderfully simple shortcut for collision detection, which ran fine on a 1 MHz 6502, with maybe a dozen game objects on the 280 x 192 pixel screen at any time. It was this. When drawing each object to the screen, perform a logical AND of each byte it with the pixels underneath it, then XOR it to the screen. After the fact, if any of the ANDs yielded a nonzero result, we know the object has collided with something. The usual response was to simply back it up to the previous position, and maybe reverse its direction if it’s a “bouncer”.

It was visually perfect: if it looks like they collide, they collide. (2)

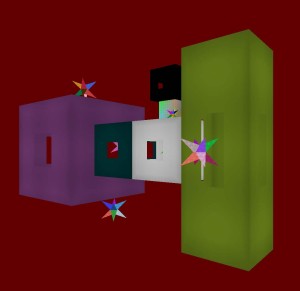

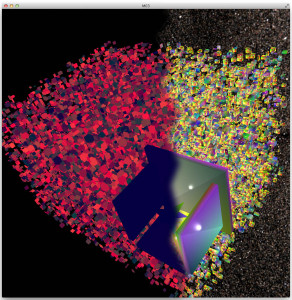

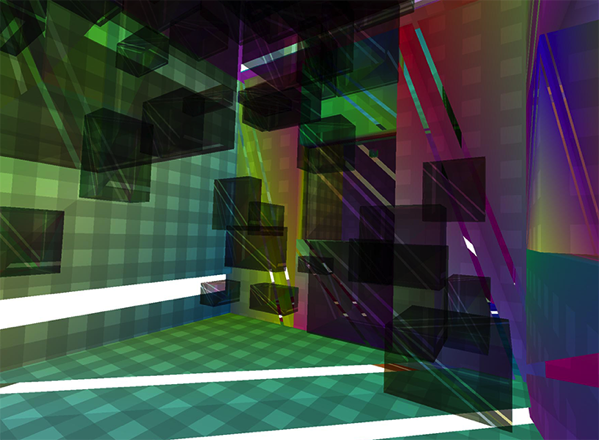

The modern world, however,

has different rules. The world is still grid-like, but may deviate in places, for dramatic effect. Your probe can move in any direction. Even, like, you know, diagonals. As clever as “pixel collision detection” may have been in 1984, it’s not the right approach any more.

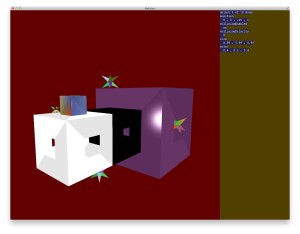

However, the walls shall all be rectangular and planar, and plane-aligned to one of XY, YZ, or ZX. And although objects may be oddly shaped, I’m comfortable treating them, for collision and detection purposes, generally as boxes as well.

In game programming, this kind of geometry is called “axis-aligned bounding-boxes”, or AABB.

The general flow for each frame is:

- Objects may move or teleport

- Collisions are assessed

- Corrections are made to conform to the world rules, like objects can’t move through walls so they need to stop at the wall.

First Problems

Iterating with the design and implementation revealed a few gotchas and false starts.

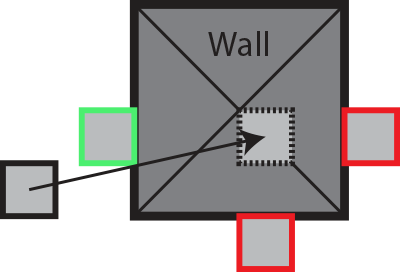

Problem: Sudden snapping looks bad!

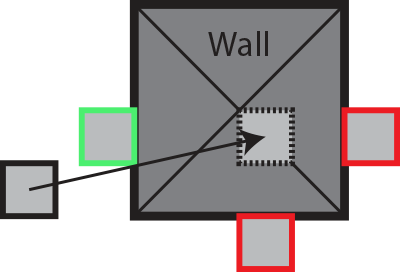

A tempting approach is to look for intersections, and find the minimal move to “fix” the intersection.

But visually, a sudden correction of your line of travel makes no sense. It feels clunky

Solution: Correction must be to move less, not more

To remain visually pleasant and plausible, a correction must only work against the movement. It mustn’t move further than the original movement, or in a different direction. (3)

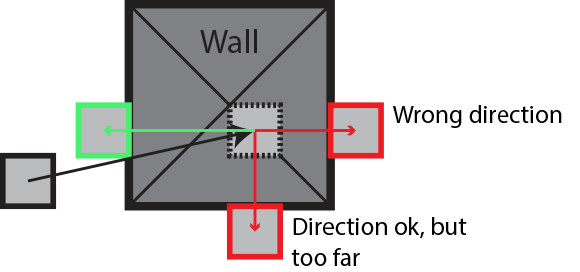

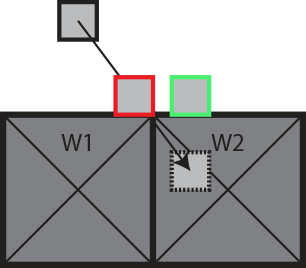

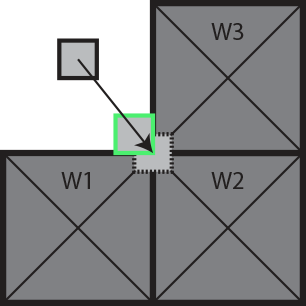

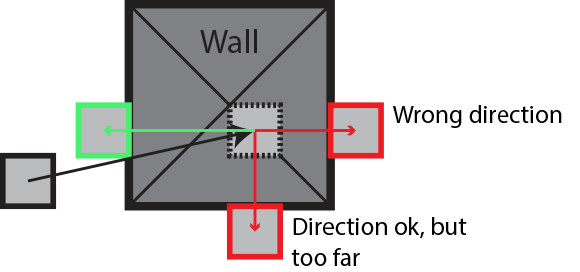

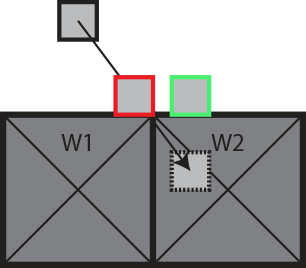

Problem: Snagging on Seams

As an object moves along a wall, pressing downward, at some point it might seem like the “minimal correction” is to stop the forward motion. At first think, doing the smallest possible correction seems best… But if we handle W2 first, then we “snag” on the wall seam.

Solution: Handle “necessary” corrections first

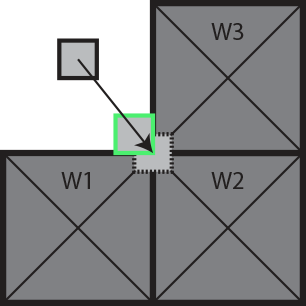

If we look at each intersection, we can see that on W1, only one correction is possible: upward. W2, on the other hand, has a choice between slightly left, or very up. Since W1 has no choice, we commit to the upward motion. Then we handle W2, which turns out to need no further correction. This also handles the case of corners:

Where each of W1 and W3 have only one viable correction. W2 had a choice, and in effect uses both of them.

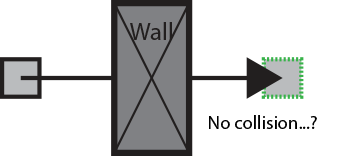

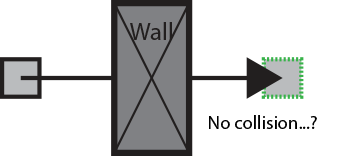

Non-Problem: Bullet Penetration

In the Metareal World, things don’t move fast. In some game worlds, we care deeply about projectiles and vehicles passing rapidly through walls. “It can’t happen here.”

<>

<>

It turns out in this world, conveniently, we don’t need to worry about it. Objects can only move a fraction of their own size per frame. (The corner example above depends on this, by the way, to not squirt “between” W1 and W3, leaving only W2 in collision.)

Implementation Details

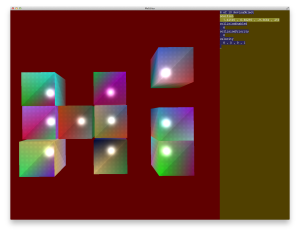

First thing to note: Metareal does this in 3d, not 2d. Everything is as shown above in the pictures, but in three axes.

The implementation is as follows (4):

- (This is done for each moving object.)

- The movement is in some direction, (Mx, My, Mz).

- For each intersection, describe a correction (Cx, Cy, Cz) that would move it out of the intersection.

- The correction shows 1 or more possible axes of correction. (-1, 2, 0) would mean that x-1 or y+2 would resolve the intersection.

- The correction is in the opposite direction from the movement. We never resolve a collision by moving even more than the original movement. This is the rule that prevents lurchy snappings.

- We go through the list of corrections. Those with a single axis of correction, like (0, 2, 0), are applied. It means there’s no alternatives to that shove, to get out of collision.

- These mandatory shoves are subtracted from the remaining possible collisions, all of which involve a choice between several possible axes. Thus modified, the smallest axis of correction for each is chosen.

If only the object is moving, and the walls are not, then the shove directions from all collisions have the same signs — in particular, opposite of the movement.

Also, if the object started out not in collision, then the greatest possible correction is simply to undo the movement. This would happen when trying to move into a corner.

Futures and Glossovers

There are still things this algorithm handles poorly.

- Each object has a priority. Walls have a higher priority than objects, for example. This is taken into account to decide which thing gets shoved.

- Transitive shoving is not well-handled yet. Ideally, this should be resolved within each frame, not rippling forward in time. Also, shove priority should be transitive as well. For example, normally a P3 object cannot push a P2 object. But if the P3 object is impelled by a P1 object into the P2 object, then, backed by the higher priority (5) force, it should successfully move the P2 object as a result.

- The actual implementation treats the movement vector as the difference between the object’s movement and the “wall’s” movement (which might not really be a wall). If these are from different directions, the corrections may be contradictory; resolution may be impossible. For now, I average them and let the object get squished between them. But it is not satisfying.

- In something resembling the “relativistic sliding hole” paradox, a sliding object can slip into gap that is smaller then itself. Then it’s once again in the “pushed from both sides” state, which doesn’t work well.

Some of these can be mostly avoided with careful world design. Transitive shoving will be implemented as part of Phase II; it will be needed.

Footnotes

1. Last night I had a dream involving a post-apocalyptic Oakland (comma, California), vast concrete parking garage-like spaces. The bedraggled, homeless denizens clustered and sat here and there, moving metal scraps and junk around on crude, chalk-drawn boards. They were in some way psychically addicted to playing chess. Anyway, the term “cardinal directions.” I wonder if Rooks ought more properly to be called Cardinals.

2. Except that on the Apple II green and purple don’t collide, they occupy alternate bits. So objects were carefully designed to have white parts at collision-ey points.

3. Sometimes an object uses “teleporting”, where it moves a great distance without expecting smooth visual continuity. In that case, it’s ok to lurch, and indeed we can just take the minimal correction in any direction to enforce the world’s physics.

4. This answer on gamedev.stackexchange.com suggests to simply resolve all your X-penetrations first, and then Y-penetrations. But I’m not convinced.

5. Since I come from an embedded hardware background, I’m accustomed to explaining that interrupts with lower numbers have higher priorities. I carry this convention forward.

<

<